Manual de Bioseguridad en el Laboratorio. 09 – Referencias, anexos e índice alfabético. Parte 1

PARTE IX – Referencias, anexos e índice alfabético

Referencias

- Safety in health-care laboratories. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1997, (http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/ 1997/WHO_LAB_97.1.pdf).

- Garner JS, Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guideline for isolation precautions in hospitals. American Journal of Infection Control, 1996, 24:24–52, (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/hip/isolat/isolat.htm).

- Hunt GJ, Tabachnick WJ.Handling small arbovirus vectors safely during biosafety level 3 containment: Culicoides variipennis sonorensis (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) and exotic bluetongue viruses. Journal of Medical Entomology, 1996, 33:271–277.

- National Research Council. Occupational health and safety in the care and use of research animals.Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1997.

- Richmond JY, Quimby F. Considerations for working safely with infectious disease agents in research animals. In: Zak O, Sande MA, eds. Handbook of animal models of infection. London, Academic Press, 1999:69–74.

- Biosafety in microbiological and biomedical laboratories, 4th ed. Washington, DC, United States Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Institutes of Health, 1999.

- Class II (laminar flow) biohazard cabinetry. Ann Arbor, MI, National Sanitation Foundation, 2002 (NSF/ANSI 49–2002).

- Richmond JY,McKinney RW. Primary containment for biohazards: selection, installation and use of biological safety cabinets, 2nd ed.Washington, DC, United States Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Institutes of Health, 2000.

- Microbiological safety cabinets. Recommendations for information to be exchanged between purchaser, vendor and installer and recommendations for installation. London, British Standards Institution, 1992 (Standard BS 5726–2:1992).

- Microbiological safety cabinets. Recommendations for selection, use and maintenance. London, British Standards Institution, 1992 (Standard BS 5726–4:1992).

- Biological containment cabinets (Class I and II): installation and field testing. Toronto, Canadian Standards Association, 1995 (Standard Z316.3–95 (R2000)).

- Collins CH, Kennedy DA. Laboratory acquired infections: history, incidence, causes and prevention, 4th ed. Oxford, Butterworth-Heinemann, 1999.

- Health Canada. Laboratory biosafety manual, 2nd ed. Ottawa, Minister of Supply and Services Canada, 1996.

- Biological safety cabinets – biological safety cabinets (Class I) for personnel and environment protection. Sydney, Standards Australia International, 1994 (Standard AS 2252.1–1994).

- Biological safety cabinets – laminar flow biological safety cabinets (Class II) for personnel, environment and product protection. Sydney, Standards Australia International, 1994 (Standard AS 2252.2–1994).

- Standards Australia/Standards New Zealand. Biological safety cabinets – installation and use. Sydney, Standards Australia International, 2000 (Standard AS/NZS 2647:2000).

- Advisory Committee on Dangerous Pathogens. Guidance on the use, testing and maintenance of laboratory and animal flexible film isolators. London, Health and Safety Executive, 1990.

- Standards Australia/Standards New Zealand. Safety in laboratories – microbiological aspects and containment facilities. Sydney, Standards Australia International, 2002 (Standard AS/NZS 2243.3:2002).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for prevention of HIV transmission in health-care settings. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 1987, 36 (Suppl. 2):1S–18S.

- Bosque PJ et al. Prions in skeletal muscle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2002, 99:3812–3817.

- Bartz JC, Kincaid AE, Bessen RA. Rapid prion neuroinvasion following tongue infection. Journal of Virology, 2003, 77:583–591.

- Thomzig A et al. Widespread PrPSc accumulation in muscles of hamsters orally infected with scrapie. EMBO Reports, 2003, 4:530–533.

- Glatzel M et al. Extraneural pathologic prion protein in sporadic Creutzfeldt- Jakob disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 2003, 349:1812–1820.

- Brown P, Wolff A, Gajdusek DC. A simple and effective method for inactivating virus infectivity in formalin-fixed tissue samples from patients with Creutzfeldt- Jakob disease. Neurology, 1990, 40:887–890.

- Taylor DM et al. The effect of formic acid on BSE and scrapie infectivity in fixed and unfixed brain-tissue. Veterinary Microbiology, 1997, 58:167–174.

- Safar J et al. Prions. In: Richmond JY, McKinney RW, eds. Biosafety in microbiological and biomedical laboratories, 4th ed.Washington, DC, United States Department of Health and Human Services, 1999:134–143.

- Bellinger-Kawahara C et al. Purified scrapie prions resist inactivation by UV irradiation. Journal of Virology, 1987, 61:159–166.

- Health Services Advisory Committee. Safe working and the prevention of infection in clinical laboratories. London, HSE Books, 1991.

- Russell AD, Hugo WB, Ayliffe GAJ. Disinfection, preservation and sterilization, 3rd ed. Oxford, Blackwell Scientific, 1999.

- Ascenzi JM. Handbook of disinfectants and antiseptics. New York, NY, Marcel Dekker, 1996.

- Block SS. Disinfection, sterilization & preservation, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001.

- Rutala WA. APIC guideline for selection and use of disinfectants. 1994, 1995, and 1996 APIC Guidelines Committee. Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, INC. American Journal of Infection Control, 1996, 24:313–342.

- Sattar SA, Springthorpe VS, Rochon M. A product based on accelerated and stabilized hydrogen peroxide: evidence for broad-spectrum germicidal activity. Canadian Journal of Infection Control, 1998, 13:123–130.

- Schneider PM. Emerging low temperature sterilization technologies. In: Rutala WA, eds. Disinfection & sterilization in health care. Champlain, NY, Polyscience, 1997:79–92.

- Springthorpe VS. New chemical germicides. In: Rutala WA, eds. Disinfection & sterilization in health care. Champlain, NY, Polyscience, 1997:273–280.

- Steelman VM. Activity of sterilization processes and disinfectants against prions. In: Rutala WA, eds.Disinfection & sterilization in health care. Champlain, NY, Polyscience, 1997:255–271.

- Taylor DM. Transmissible degenerative encephalopathies: inactivation of the unconventional causal agents. In: Russell AD, Hugo WB, Ayliffe GAJ, eds. Disinfection, preservation and sterilization, 3rd ed. Oxford, Blackwell Scientific, 1999:222–236.

- Infection control guidelines for hand washing, cleaning, disinfection and sterilization in health care, 2nd ed. Ottawa, Laboratory Centre for Disease Control, Health Canada, 1998.

- Springthorpe VS, Sattar SA.Chemical disinfection of virus-contaminated surfaces. CRC Critical Reviews in Environmental Control, 1990, 20:169–229.

- Recommendations on the transport of dangerous goods, 13th revised edition, New York and Geneva, United Nations, 2003, (http://www.unece.org/trans/danger/ publi/unrec/rev13/13files_e.html).

- Technical instructions for the safe transport of dangerous goods by air, 2003–2004 Edition. Montreal, International Civil Aviation Organization, 2002.

- Economic Commission for Europe Inland Transport Committee. Restructured ADR applicable as from 1 January 2003. New York and Geneva, United Nations, 2002, (http://www.unece.org/trans/danger/publi/adr/adr2003/ ContentsE.html).

- Infectious substances shipping guidelines. Montreal, International Air Transport Association, 2003, (http://www. iata.org/ads/issg.htm).

- Transport of Infectious Substances. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2004, (http://www.who.int/csr/ resources/publications/WHO_CDS_CSR_LYO_2004_9/ en/).

- Berg P et al. Asilomar conference on recombinant DNA molecules. Science, 1975, 188:991–994.

- European Council. Council Directive 98/81/EC of 26 October 1998 amending Directive 90/219/EEC on the contained use of genetically modified microorganisms. Official Journal, 1998, L330:13–31.

- O’Malley BW Jr et al. Limitations of adenovirus-mediated interleukin-2 gene therapy for oral cancer. Laryngoscope, 1999, 109:389–395.

- World Health Organization. Maintenance and distribution of transgenic mice susceptible to human viruses: memorandum from a WHO meeting. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 1993, 71:497–502.

- Furr AK. CRC handbook of laboratory safety, 5th ed. Boca Raton, FL, CRC Press, 2000.

- Lenga RE. The Sigma-Aldrich Library of Chemical Safety Data, 2nd ed.Milwaukee, WI, Aldrich Chemical Company, 1988.

- Lewis RJ. Sax’s dangerous properties of industrial materials, 10th ed. Toronto, John Wiley and Sons, 1999.

ANEXO 1 – Primeros auxilios

Los primeros auxilios consisten en la aplicación experta de principios aceptados de tratamiento médico en el momento y el lugar en que se produce un accidente. Es el método aprobado para tratar a la víctima de un accidente hasta que se la pueda poner en manos de un médico para el tratamiento definitivo de la lesión.

El equipo mínimo de primeros auxilios consta de un botiquín, ropa protectora y equipo de seguridad para la persona que presta los primeros auxilios, y equipo para la irrigación ocular.

El botiquín de primeros auxilios

El maletín propiamente dicho debe estar hecho de un material que mantenga el contenido sin polvo ni humedad. Debe guardarse en un lugar bien visible y ser fácilmente reconocible. Por convenio internacional, el botiquín de primeros auxilios se identifica mediante una cruz blanca sobre fondo verde.

El botiquín de primeros auxilios debe contener lo siguiente:

- Hoja de instrucciones con orientaciones generales

- Apósitos estériles adhesivos, empaquetados individualmente y de distintos tamaños

- Parches oculares estériles con cintas

- Vendas triangulares

- Compresas estériles para heridas

- Imperdibles

- Una selección de apósitos estériles no medicados

- Un manual de primeros auxilios, por ejemplo publicado por la Cruz Roja Internacional.

El equipo de protección de la persona que presta los primeros auxilios incluye lo siguiente:

- Una gasa para la boca para realizar la respiración boca a boca.

- Guantes y otras protecciones de barrera contra la exposición a la sangre.1

- Un estuche de limpieza para los derrames de sangre (véase el capítulo 14 del manual).

También debe disponerse de material para la irrigación ocular; el personal estará debidamente adiestrado en su utilización.

1 Garner JS, Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guideline for isolation precautions in hospitals. American Journal of Infection Control, 1996, 24:24–52, (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/hip/ isolat/isolat.htm).

ANEXO 2 – Inmunización del personal

Los riesgos que entraña trabajar con ciertos agentes deben explicarse de forma completa a cada investigador. Antes de comenzar a utilizar posibles vacunas o agentes terapéuticos (por ejemplo, antibióticos) en caso de exposición, deberá evaluarse su disponibilidad local, si están aprobados y su utilidad. Algunos trabajadores pueden haber adquirido inmunidad en una vacunación o infección anteriores.

Si una vacuna o un toxoide particular están aprobados y disponibles localmente, deben ofrecerse después de evaluar el riesgo de una posible exposición y de proceder a una evaluación clínica de la persona afectada.

También deben existir instalaciones para la gestión de casos clínicos particulares después de una infección accidental.

ANEXO 3 – Centros colaboradores de la OMS en materia de bioseguridad

Puede obtenerse información sobre la disponibilidad de cursos de formación y material didáctico y auxiliar escribiendo a cualquiera de los siguientes centros:

- Programa de Bioseguridad. Departamento de Enfermedades Transmisibles (Vigilancia y Respuesta), Organización Mundial de la Salud. 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Ginebra 27 (Suiza) (http://www.who.int/csr/).

- Centro Colaborador de la OMS sobre Seguridad Biológica. Instituto Sueco de Lucha contra las Enfermedades Infecciosas,Nobels Väg 18, S-171 82 Solna (Suecia). (http://www.smittskyddsinstitutet.se/English/english.htm).

- Centro Colaborador de la OMS sobre Tecnología de Bioseguridad y Servicios Consultivos, Oficina de Seguridad en el Laboratorio. Health Canada. 100 Colonnade Road, Loc.: 6201A, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0K9 (Canadá) (http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/pphb-dgspsp/ols-bsl).

- Centro Colaborador de la OMS sobre Capacitación y Programas de Bioseguridad Aplicada. Oficina de Salud y Seguridad, Centros para el Control y la Prevención de Enfermedades. 1600 Clifton Road, Mailstop F05, Atlanta, GA 30333 (Estados Unidos de América) (http://www.cdc.gov/).

- Centro Colaborador de la OMS sobre Programas de Bioseguridad Aplicada. Departamento de Seguridad y Salud Ocupacional, Oficina de Servicios de Investigación, Institutos Nacionales de la Salud. 13/3K04 13 South Drive MSC 5760, Bethesda, MD 20892-5760 (Estados Unidos de América) (http://www.nih.gov/).

- Centro Colaborador de la OMS sobre Bioseguridad. Laboratorio de Referencia de Victoria para las Enfermedades Infecciosas. 10 Wreckyn St., Nth Melbourne, Victoria 3051 (Australia). Dirección postal: Locked Bag 815, PO Carlton Sth, Victoria 3053 (Australia) (http://www.vidrl.org.au/).

ANEXO 4 – Seguridad del material

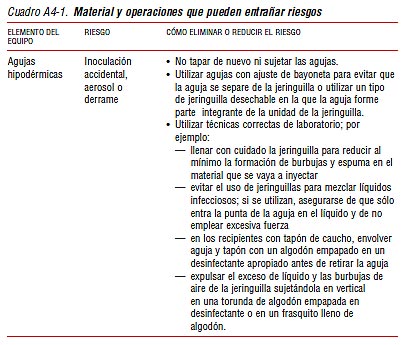

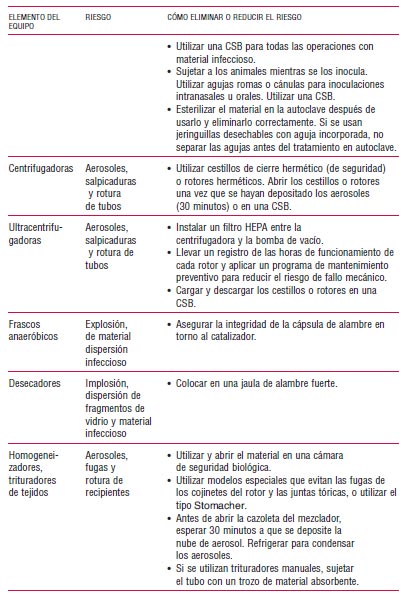

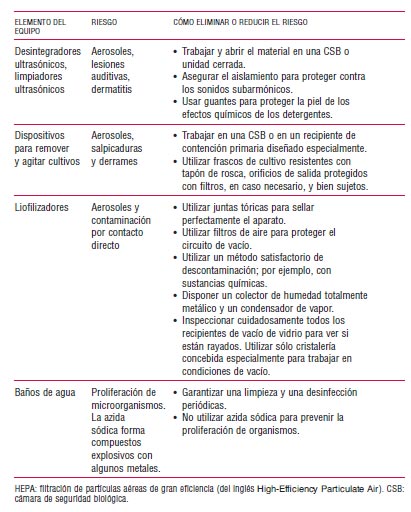

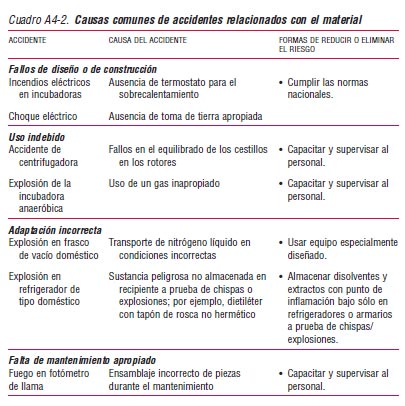

Ciertos elementos del material de laboratorio pueden entrañar riesgos microbiológicos durante su utilización. Otros elementos están específicamente diseñados para evitar o reducir los riesgos biológicos (véase el capítulo 11 del manual).

Material que puede ser peligroso

En el cuadro A4-1 se enumeran el material y las operaciones que pueden crear riesgos y se sugieren formas de eliminar o reducir esos riesgos.

Además de los riesgos microbiológicos, también es necesario prever y prevenir los riesgos de seguridad asociados al equipo propiamente dicho. En el cuadro A4-2 se enumeran algunas causas de accidentes.

|

|

Fuente: OMS – Organización Mundial de la Salud